Albemarle Barracks: A Piece of the Revolution Lives in Charlottesville

Albemarle Barracks: A Piece of the Revolution Lives in Charlottesville

Ever wonder how Barracks Road got it’s name? Now home to grocery stores, restaurants, and houses, the area was once home to an army barracks. It used to house prisoners of war during the American Revolution. British General John Burgoyne suffered a decisive defeat at the hands of American soldiers in the Battle of Saratoga (1777). In the aftermath of the battle, the colonies took 4,000 prisoners (2,000 British soldiers, 1,900 Hessian (German mercenary) soldiers and 300 women and children.) The original plan was to house them in Cambridge, Massachusetts, but the Continental Congress decided to send them south instead. One of the Congressmen, Colonel John Harvie/Harvey had property in Albemarle County, on land north of Charlottesville, and he offered it up.

In Flight from Monticello: Thomas Jefferson at War, author Michael Kranish writes about the barracks in some detail. Thomas Jefferson believed that the influx of these soldiers would bolster the city’s economy, and he had high hopes for the cultural offerings of the British and Hessian officers. In addition to a great many talents, Jefferson was an avid violinist, and in the prisoners, he hoped to find some musical peers. Despite good intentions, the encampment was ill-equipped to handle 4,000 new people. Morale was already low among the prisoners after a long, exhausting journey south, and seeing the condition of the barracks didn’t help. However, the British and Hessian soldiers made a home in Charlottesville, fixing up the embankment, raising livestock, building a store, a cafe, bar, church, and even a theater! They essentially assimilated to the idyllic nature of life in Charlottesville.

In the Hessians, Jefferson finally found musicians with whom he could play. He also formed friendships with the German Baron Frederick von Riedesel and British General William Phillips, commanding officers of the defeated troops. And he estimated that the city was generating the modern-day equivalent of $300,000 a week because the prisoners were being housed in Charlottesville. However the embankment was not well-equipped. Most of the improvements were made by the prisoners themselves, and they had no real incentive to make the place secure. They were treated well by Jefferson and his men, but the barracks were infamous for allowing prisoners to escape. Prisoners were even allowed to go into the city, developing a familiarity with the surroundings that could have been advantageous in a British attack on the city. Eventually Jefferson received an angry correspondence from General George Washington, who claimed that several British and Hessian soldiers were simply walking around the streets unguarded, making themselves at home in Charlottesville. Many Hessian soldiers simply left the embankment, found American jobs and wives, and settled down. In 1779, Jefferson had become governor of Virginia, and so Washington held him directly responsible. Eventually General Phillips and Baron von Frederick were exchanged for two American officers. The following year, Jefferson closed the barracks. The remaining prisoners were sent north to Frederick Maryland, or Winchester. In 1781, Phillips returned to Virginia with the traitor Benedict Arnold to capture Jefferson. TJ narrowly escaped Richmond as it burned.

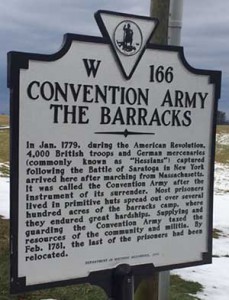

Today, the original site of the barracks is located on private property north of Charlottesville. It’s recognized by a Virginia state historical marker. In 1983, the Albemarle County Historical Society built a plaque commemorating the barracks. To see the marker, head west of town on Barracks Road to Barracks Farm Road. The marker is a little north of Ivy Farm Drive.